I was in my twenties before I discovered TC, which is surprising since, by that time, I had struggled to support a grievous book-a-day, largely indiscriminate reading habit for years. Indeed, I had for some time been unable to afford buying enough literature to serve my growing dependence, and was forced to skulk around libraries wheedling texts. I'd read anything.

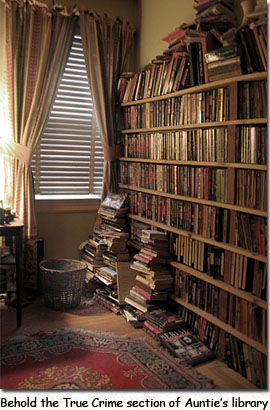

But in those long-ago halcyon days of misty yesteryear, there was no explicit True Crime section. Not in libraries, not in bookstores. The pulpy world of non-fiction crime was too icky and low-rent to be rewarded with its own shelf space and what few works were available were hidden among the books in Social Sciences (Dewey Decimal 300-310) or Law (DD 340-350). And slim pickings there, unless you like Truman Fucking Capote.

I ran across my first quite by accident (In His Garden by Leo Damore, and I do recommend it), while cruising Law. I was hooked from the start.

I ran across my first quite by accident (In His Garden by Leo Damore, and I do recommend it), while cruising Law. I was hooked from the start.

Only later did I discover the tragic genetic link. My mother and my mother's mother were enthusiastic readers of TC, as is my father, his sister and her daughter (not my brother, though. Whew! That would be scary). My stepmother once confided in me that our family taste for the gruesome so worried her, in the event of her sudden death an autopsy is directed in her will. (Ha ha! Silly woman! As though we have learned nothing of eluding chemical analysis in our years of study).

For some reason, the popularity and availability of True Crime took off in the 1990s. I think that's because we as a society finally did away with the outmoded concept of "shameful" and replaced it with "differently honorable." Okay, now I'm channeling John Dunning. Scary. Let's move along. So, what draws people to an appreciation of true crime?

Morbid Curiosity

I mention this one first because otherwise Uncle Badger would accuse me of trying to gloss over it. He's convinced morbid curiosity the only reason anyone would read morbid stories. Still, I think he's finally gotten over being physically afraid of me, and he buys me lots of grisly murder books for my birthday (the classic ones from England with the big words in), so that's okay.I won't deny that I find the ghastly interesting for its very ghastliness. When I was seven, I spent my two days in Grand Teton National Park sitting on a rock poking a dead rat with a stick. My parents liked to tell that story (god knows why...if it were my kid, I'd be trying to hush it up). But when you get right down to it, there are really only two kinds of people in this world: those who could happily spend two days in Grand Teton National Park sitting on a rock poking a dead rat with a stick, and ugly stupid people.

There. Somebody had to say it.

For a Glimpse Inside the Minds of Low-Lifes and Nuts

It's amazing what people will do to each other, with each other, to and with themselves, for money, for sex, for no discernable reason, for reasons so strange you can't quite hold them in your head, in anger, in lust, in fear or in howling madness. That people can be terribly crazy or terribly evil is no surprise, though the breadth and depth of it is astonishing. But it's sometimes the terrible, pointless casualness of the killing that surprises most. Murder is such a bad solution to almost any problem, and yet, again and again, it strikes someone as the easiest way out of a jam.If you like biography and are a student of the species, but you think movie stars and politicians and other famous people are mostly stupid, boring jerks; if you find the lives of prostitutes and carnies (who are supposed to be stupid jerks) intrinsically more interesting, then true crime is for you. It's the celebrity of life's losers.

For a Snapshot of History

I don't know any documentation of the past that is as usefully particular and as descriptive of the ordinary as true crime. Trial transcripts literally empty a dead man's pockets. Where else can you learn what time a scullery maid had to get out of bed in Yorkshire in 1863, or how much de fric a Parisian waiter made in 1910?Except history books. But those are boring.

For its Grim Poetry

I like collections of true crime. They tend to be made of the same favorite short stories over and over again, and there's a certain afficionado's pleasure in that. Journalists are a lazy lot and crib from each other generation after generation, so parts of the story become hardened through repetition and polished into a kind of verse. Certain facts repeat, certain phrases recur, certain descriptions are always used, with certain photos run alongside. It's what I imagine happens to a theme when it is part of an oral tradition: always the same in some ways, unique to the teller in others. Like Beowulf. Or the Icelandic Sagas.And every classic murder has at least one chilling fact, one oft-repeated ghastly detail, that separates it from the tens of thousands of murders no-one ever heard of, and makes it a classic. Ghastly detail: when police entered the apartment of Joachim Kroll, they found a saucepan simmering on the stove containing peas, carrots and the hand of a four-year-old girl. See? It is the homely, cheerful peas and carrots that make the little hand so awful.

And there's mostly an agreed nomenclature, too. You say "Luton" I think "Sack Murder." England is especially good for this. In fact, I'm able to navigate entirely by way of famous murders. Do we pass the Eastbourne Bungalow Murder on the way to the Brighton Trunk Murder? You bet we do! As someone with a poor sense of direction but a very good memory for the horrible, this has been much very handy.