The Portuguese Escudo: 1911 – 1999

Portuguese escudos. What? It came up in a thread, so I figured I’d dig out a few.

“Escudo” means “shield” in Portuguese. The denomination was adopted in 1910, after the Republican revolution. It replaced the real. There are 100 centavos in an escudo, and escudo amounts are written escudos$centavos (except it isn’t really a dollar sign in the middle; theirs has two strokes).

The escudo was in trouble in the early 20th C, especially after a counterfeiting operation was traced to the Bank of Portugal. Oops. Eventually it stabilized and was pegged to the British pounds, then the US dollar and finally abandoned for the stupid Euro.

That lady looks familiar. I think she’s a smurf.

I have the world’s stupidest coin collection; nothing I own is worth anything. I just like to play with moneys.

May 1, 2008 — 12:14 pm

Comments: 48

Ben sez: None of your beeswax

Okay, one more coin. This is the Continental Dollar; the very first coin of the brand new United States. It was designed — couldn’t you guess by looking at it? — by Ben Franklin.

The motto “Fugio” (I fly) together with the sundial means “time’s a-wasting.” This motto also appeared on the penny at right some years later; it’s often called the “Fugio” penny. Check out the goofy little R. Crumb face on the suns.

It isn’t certain whether Ben meant “Mind Your Business” as in “you there! Look to your factories and your warehouses, Sir” or “sticketh not thy snout where it should’st not be.” With Franklin, it could go either way.

April 3, 2007 — 11:58 am

Comments: 19

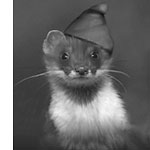

Liberté – Egalité – Mustelidité

So, about Phrygian caps. Phrygia was an ancient kingdom in what is modern Turkey. It was conquered repeatedly by its neighbors, the ancients tell us, “for wearing those dumbass hats.” In Greek art, the Phrygian cap was used to indicate the wearer was some kind of foreigner, and Roman poets referred to Trojans as Phrygians. I claim extra credit for not making a cheap Trojan/hat joke.

So, about Phrygian caps. Phrygia was an ancient kingdom in what is modern Turkey. It was conquered repeatedly by its neighbors, the ancients tell us, “for wearing those dumbass hats.” In Greek art, the Phrygian cap was used to indicate the wearer was some kind of foreigner, and Roman poets referred to Trojans as Phrygians. I claim extra credit for not making a cheap Trojan/hat joke.

Anyhoo, the Phrygian cap was like a red nightcap with the point pulled forward. The next time it turns up in history, it’s being worn by freemen of Rome — former slaves whose freedom was so thorough, it would be passed to their children. And that’s where the hat became associated with freedom and liberty.

Anyhoo, the Phrygian cap was like a red nightcap with the point pulled forward. The next time it turns up in history, it’s being worn by freemen of Rome — former slaves whose freedom was so thorough, it would be passed to their children. And that’s where the hat became associated with freedom and liberty.

Like this lady, the tart with the titties (hoo boy! Googleanch, here I come!). The spirit of France is called Marianne, and she’s usually drawn wearing a Phrygian cap (or Bonnet Phrygien, eef you pleez). Here she is, flashin’ ’em for the troops.

Woohoo, Marianne! And Ginger, too!

Phrygian caps were an essential symbol of the American Revolution, usually waved about on a stick, called a Liberty Pole. The Sons of Liberty in New York, before the Revolution, were professional Liberty Pole putter-uppers. They’d put ’em up, the Brits would tear ’em down. It was zany, madcap revolutionary fun. With occasional violence!

Phrygian caps were an essential symbol of the American Revolution, usually waved about on a stick, called a Liberty Pole. The Sons of Liberty in New York, before the Revolution, were professional Liberty Pole putter-uppers. They’d put ’em up, the Brits would tear ’em down. It was zany, madcap revolutionary fun. With occasional violence!

Hence, several early American coins pictured Liberty wearing the cap or waving it about on a stick. Unfortunately, our available pool of Revolutionary-era artists was not so hot, and the caps look hilariously like panties. Panties! On her head! Waved about on a stick! Allegorical Girls Gone Wild!

The cap still appears in the official seals of the US Army and the US Senate (which also features a bonus pair of crossed fasces). Plus the state flags of New York, New Jersey and West Virginia.

The panty craze swept Southward, with Phrygian caps appearing on the coins of Mexico and the flags or coats of arms of Cuba, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Colombia, Haiti, Argentina and Paraguay. ¡Caramba!

And then there’s the Smurfs. Really, I have no smurfing idea what that’s all about.

March 28, 2007 — 9:56 am

Comments: 12

Our tiny silver numismatic mixed metaphor

I love the mercury dime. Both for the beautiful design by Adolph Alexander Weinman, and the brain-hurtingly odd symbolism.

These were still in circulation when I was a kid, but it was a rare and wonderful thing to get one. It would be too cool if the dude on it were actually Mercury, since Mercury is the god of business and trade. His name is derived from merx — as are the words commerce, merchant and merchandise. But, no. It’s not a dude! It’s a chick! Specifically, it’s this lady, Elsie Kachel Stevens. She was the wife of poet Wallace Stevens. Wallace commissioned Weinman to do her portrait and got two and a half billion of them. Pretty good value for money.

These were still in circulation when I was a kid, but it was a rare and wonderful thing to get one. It would be too cool if the dude on it were actually Mercury, since Mercury is the god of business and trade. His name is derived from merx — as are the words commerce, merchant and merchandise. But, no. It’s not a dude! It’s a chick! Specifically, it’s this lady, Elsie Kachel Stevens. She was the wife of poet Wallace Stevens. Wallace commissioned Weinman to do her portrait and got two and a half billion of them. Pretty good value for money.

Check out the jaw on that lady! This could almost be a picture of my paternal grandmother, a woman of the same age and time. It’s funny how eras have faces and faces have eras.

Anyhow, here Elsie represents Liberty. That’s a phrygian cap on her head (the one on the coin, not the one in the picture), a bit of old Roman symbolism often used to represent liberty or freedom. It appears in a lot of early American iconography. The wings, however, are unique to this particular design; they symbolize freedom of thought. Okay, got that? The obverse of this coin represents freedom of thought.

Right, so what’s that thing on the back? It’s an olive branch wrapped around the fasces — a bundle of birch sticks bound to an axe. It’s an icon that dates back, possibly, to the Etruscans. Actual fasces were carried in procession in Roman times. The fasces symbolize strength through unity (the rods bound together) or alternatively the power of the state (birch rods, axe: whipping, decapitation. The state has the power of life or death over you, get it?).

Yes, as in fascism. Benito Mussolini coopted the term, both to evoke the fasces of Rome and the modern Italian word fascio, which means union or league. But you can’t blame poor old Weinman for that; fasces are all over our national symbols and state flags. Still are. And Weinman designed this in 1915.

So what’s going on here? Free thought, peace, the power of the state? Well, this coin was a message to Europe, then one year into World War I. Not that they knew that’s what it was going to be called yet, but we wanted no any part of whatever you call it. This coin was meant to say, we think for ourselves and we like peace, but if you screw with us, Europe, we swear to god we’ll cut you good.

Now we know how that worked out for us: Elsie Kachel Stevens and her smurf hat got to circulate through two European wars, and we got drawn into them both.

One of which I am not. I just like coins. This is not a collector quality coin (very few of mine are). The fine specimens are all about the bands around the fasces: if you can see that they’re split into multiple cords (“full split bands”), it’s a high quality specimen.

March 26, 2007 — 7:23 am

Comments: 9